Nextflow Scatter Gather

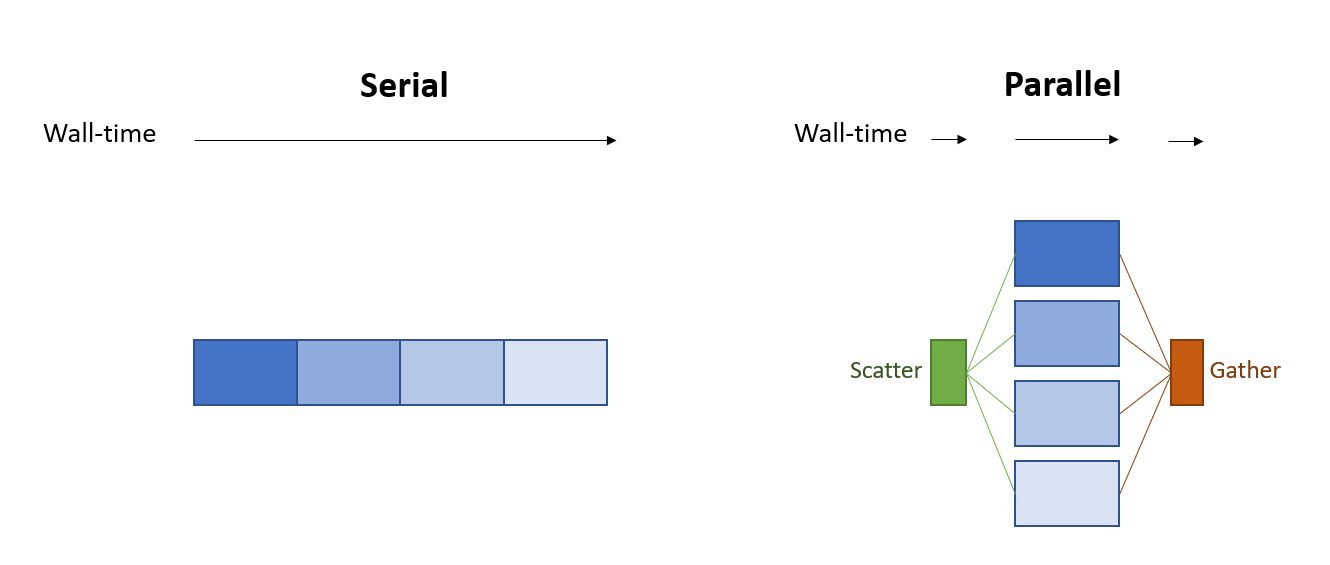

Sometimes when building a workflow you’ll run into a situation where one of the steps in your workflow takes much longer than it should (or at least longer than you wish it would). If you are lucky, the problematic task is “embarassingly parallelizable” and you can easily accelerate the analysis by splitting the work performed by the slow process into smaller pieces that are run in parallel, as illustrated below:

One place this scatter/gather strategy can come up in bioinformatics is when pre-processing a large number of reads. For example, when evaluating a gene-edited cell therapy product we need to characterize the off-target effects of the sequence-programmable nuclease (e.g. Cas9) used to perform the editing. If the guide selected for editing has low homology to genome sequences outside of the target site then off-target cutting events will be rare, and detecting rare events such as CRISPR off-target editing or translocations can require sequencing tens of millions of reads. To manage PCR duplicates library preparation strategies add UMIs to the DNA library. UMI-tools is a popular tool for working with UMIs, but as of the time of writing this, it only supports single-thread processing. When processing millions of reads with a single thread UMI assignment becomes the most time consuming step in many workflows.

Luckily, to assign a UMI you only need the information in the read sequence, which means the process can be run in parallel by splitting the FASTQ file into chunks and running the computation across more CPUs. As it turns out, using Nextflow it only takes a few lines of code to convert an arbitrary single-threaded process into one that executes in parallel using the channel operators flatMap() and groupTuple().

Implementing Scatter/Gather in Nextflow

For the sake of illustration, imagine you have a process for running UMI-tools on a FASTQ file:

process UMI_tools {

input:

tuple sample_id, path('in.fastq.gz')

output:

tuple sample_id, path('umis.fastq.gz'), emit: UMIs

script:

// elided code that extracts UMIs using UMI_tools

}

Given this process definition, an initial workflow that processes FASTQ files using UMI-tools in a single thread per UMI-tools process would be:

fastqs = Channel.fromList(

[

['sample1', 'sample1.fastq.gz'],

['sample2', 'sample2.fastq.gz']

]

)

workflow {

UMI_tools( fastqs )

}

To implement the scatter/gather strategy the UMI-tools process is sandwiched between two processes that reshape the data to enable parallel processing:

N_PIECES = 10

workflow {

// Scatter

SplitFastq( fastqs, N_PIECES )

fastq_pieces = SplitFastq.out.pieces.flatMap {

sample_id, chunk_list -> chunk_list.collect {

chunk -> tuple( sample_id, chunk )

}

}

// Apply

UMI_tools( fastq_pieces )

// Gather

GatherFastq( UMI_tools.out.UMIs.groupTuple( size: N_PIECES ) )

}

Where the SplitFastq and GatherFastq processes are defined:

// process that splits a FASTQ file into `n_pieces`

process SplitFastq {

input:

tuple val(sample_id), path("in.fastq.gz")

val( n_pieces )

output:

tuple val(sample_id), path("piece*"), emit: pieces

script:

"""

zcat in.fastq.gz | \

StreamSplitter write -chunkSize 4 \

-n ${n_pieces} \

-base piece

"""

}

// process to combine the pieces of a split FASTQ back together

process GatherFastq {

input:

tuple sample_id, path("piece*.fastq.gz")

output:

tuple sample_id, path("gathered.fastq.gz"), emit: gathered

script:

"""

cat piece* > gathered.fastq.gz

"""

}

The “StreamSplitter” command used to implement the scatter step is not a standard command line utility. For brevity I will not be going into it here, but at a high level it is like the linux utility csplit, with the difference that it creates a specified number of files rather than output files with a fixed size.

If you have not spent a lot of time with Nextflow’s Channel operators the hairiest step of implementing scatter gather is likely where the data is reshaped using “flatMap()”:

fastq_pieces = SplitFastq.out.pieces.flatMap {

sample_id, chunk_list -> chunk_list.collect {

chunk -> tuple( sample_id, chunk )

}

}

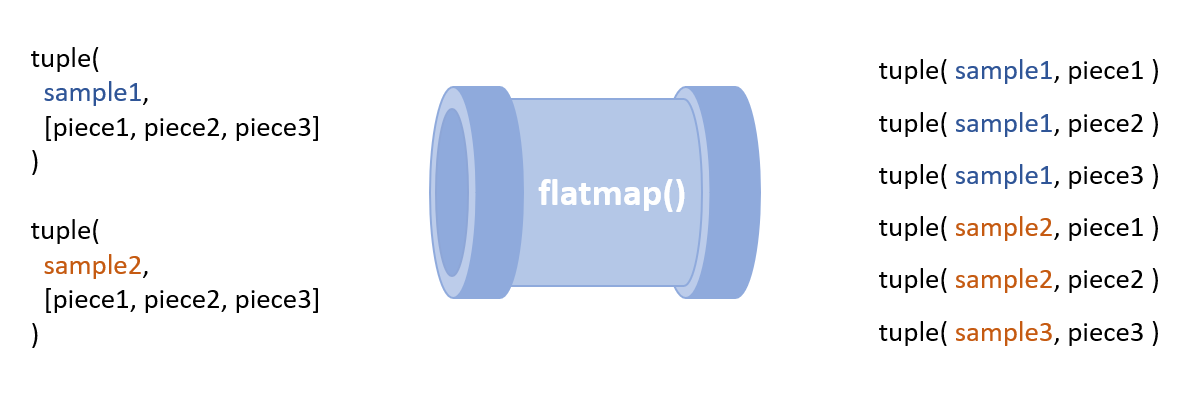

To break this down, it is important to note that

for a single set of inputs a Nextflow process

will emit a single “message” into its output

channel. The SplitFastq task emits messages that

contain a tuple of the sample_id and the list of

FASTQ file chunks created by the split

operation. In order to process each chunk in

parallel the list of chunks needs to be

separated into individual messages that can be

analyzed in parallel. The

flatMap() operation reshapes the

messages from the SplitFastq by converting from

large messages that each contain a lists of

FASTQs into many messages each containing a

single piece of the FASTQ. The

collect() operator is used to ensure

the

sample_id

associated with a FASTQ file is propagated to

each of the FASTQ pieces. For those who are more

visually inclined the transformation is

illustrated below:

Maintaining flow

One last detail to call out is the importance of

the

groupTuple(size:)

parameter. Nextflow channels do not “know” how

many elements are associated with each key used

for grouping (in the example above the

sample_id

is the grouping key). Because of this Nextflow

will wait for all of the processes

before the groupTuple operation to complete

before executing any of the downstream

processes. Providing the cardinality of the

grouping to groupTuple using the

size

parameter enables Nextflow to execute the gather

processes as soon as the inputs are available,

ensuring your pipeline maintains good flow!

Summary

If you have a single-threaded process that is slowing down your pipeline and the problem you are working on is embarrassingly parallel at the input-level (e.g. FASTQ) Nextflow makes implementing scatter/gather parallelization a breeze. While it may feel like a “hack” to use scatter/gather on FASTQ chunks to accelerate your workflow this way, there is a more generous view: this strategy enables the complexities of parallel processing to be delegated to the execution engine (Nextflow, AWS Batch), allowing the core scientific logic to be kept focused, simple, and single threaded. This separation of concerns helps to keep your code maintainable and readable without compromising on performance.

Note on cost

One neat thing about the scatter/gather strategy is that it is cost-neutral; you pay for the same total number of CPU hours to run the workflow, they just run in parallel rather than sequentially. If you are running your workflow with on-prem infrastructure the number of CPUs in your cluster will limit the amount of acceleration possible. This gives managed batch compute cloud services a distinct edge since they take care of scaling your compute cluster to the size of your workload, and you do not need to pay the upkeep to maintain a large cluster to serve spiky and variable demand.

As long as the scatter and gather steps run quickly you will pay pennies of overhead for parallelization in return for hours of wall-time shaved off your workflow executions.

A final bit of unsolicited advice

Every line of code written increases the surface area where a bug can hide, raises the maintenance burden when making a change, and steepens the learning curve when on-boarding new team members to a project. While Nextflow makes implementing scatter/gather optimization for a genomics pipeline very easy, I recommend carefully evaluating whether the benefits of parallelization justify the tradeoffs. Use this pattern judiciously, avoid premature optimization!

Comments